Roberto Serpieri (University Federico II, Naples)

Download Serpieri Attach

Roberto Serpieri is Full Professor of Sociology of Education and Education Policy at the Department of Social Sciences, University Federico II, Naples, Italy. Email: profrobertoserpieri@gmail.com and his current interests of study and research concern governmentality studies in education, patterns of leadership and institutions of governance in the educational and social policies; paradigms of structuration, neo-institutionalism and analytic dualism and the analysis of the actor–structure relationship. See his publications at: www.docenti.unina.it/roberto.serpieri

The lecture discusses how the policies of leadership represent a key dispositif (device) for neo-liberal school reforms. In a foucauldian perspective, the concept of dispositif is presented as playing a strategic role at the intersection of governmentality, regimes of truth, and subjectivation. In fact, the dispositif is a historical formation of heterogeneous elements as discourses, institutions, rules, scientific knowledge(s). We could define it as a contextual and mobile configuration (see Revel 2015) of techniques of government. The dispositif is then grounded on a new conception of power, challenging its ideological function and distinguishing itself from other conceptions of State apparatus, such as the ‘Ideological State Apparatuses’ (Althusser 1970).

As for the specific field of educational leadership the lecture shows how this dispositif involves knowledge(s), practices and technologies that situate head teachers as subjects (and objects) either for the enactment of educational policies or for leading schools as organizations. In doing so, we should weaken the emphasis on ideological role of leaders; that is on leaders as part of those ‘intellectuals/high rank civil servants’ of the State, who play a crucial function in maintaining the bourgeois hegemony (cfr. Buci-Glucksman 1975).

Thus, in order to adopt a beyond ‘ideology’ perspective in a Foucauldian way, the lecture:

- shows the centrality of dispositif: in particular it discusses the way in which Foucault distances himself from ideology, in his concern with power and knowledge as it evolves towards regimes of truth and forms of subjectivation.

- illustrates the knowledge(s) about educational leadership developed, since the 80s of the last century, drawing on both organisational and managerial sciences; it also higlights the reactions to leadership coming from critical scholars; this requires two interpretative dimensions: discursive and epistemic;

- demonstrates how these knowledges are linked to forms of governmentality which shape leadership dispositif through policies, technologies and practices of training, organization and assessment that subjectivate the head teachers;

- proposes a critical deconstruction of the dispositf, in order to ‘identify emerging ‘potentials’ (Gronn 2009) of democratic leadership, as well as knowledges based on alternative truths.

The ideological suspect

Foucault’s analysis rejects ideology as the proper tool which enables us to understand the evolution of forms of knowledge, as well as they are intertwined with practices of power. Olssen (1999: 127) has noted how:

In place of such a view which distinguishes ideology from science or truth, Foucault substitutes his theoretical notion of “discursive practice” based on a minute and detailed analysis of practices that make particular forms of historical practice possible. The concept of discursive practice does not dissolve truth but rejects the distinction between ideology and truth or ideology and science. As our identities and our bodies are constructed through such discursive practices, the partitioning of truth from falsehood is problematic”.

Foucault reacts to Althusser’s conception of ideology through the discovery of the ‘formidable’ knowledge (savoir) regarding the social crime enemy (a discovery that pairs the ‘formidable’ one regarding the ‘dissoluteness’ at the origin of theories of desire, including psychoanalysis), which has to be understood in terms of relations of power (at the time still ‘disciplinar’) (PS: 133). Here a different conception of power is in play: ‘power is not conceivable as an instrument, as something possessed, nor as an ideological apparatus, but must be thought of as a primary and constitutive factor’ (Harcourt 2015: 288). Foucault proposes a more fluid conception instead of the State apparatus model: ‘an intra-state system’ or ‘relays-multipliers of power, (PS: 209) where the emergence of the idea of the State as an ‘episode in governmentality’ (STP: 248, im) comes to the fore; whereas ‘[t]he state is nothing else but the mobile effect of a regime of multiple governmentalities’ (BBP: 75, im)

Thus three implications relevant: firstly, the abandonment of a conspiracy theory of the leading class and of the bourgeois hegemony like in Gramsci. Secondly and methodologically, there is no ‘unspoken’ and invisible’; in the discourse ‘both a certain transparency and certain forms of exclusion […] are integral part of the analysis and transparency may be so transparent to obscure’ (Harcourt 2015: 289). Thirdly ‘ideology stands in a secondary position relative to something which functions as its infrastructure, as its material economic determinant, etc. For these three reasons, I think that this is a notion that cannot be used without circumspection’ (TP: 118, im).

Therefore it is in the transition to the genealogical phase that the analysis of the practices focuses more clearly not only on the knowledge (savoirs), but on ‘regimes of truth’ intertwined with power relations which make the dispositif a central knot for Foucault’s theory of the power/govern. Dispositif – that in the following section will be useful to interpret leadership policies – becomes central to biopolitics and governmentality, well beyond the couple knowledge/power still linked to the conception of the ‘disciplinary society’ (which finds its acme between The Punitive Society and Discipline and Punish). Here, with a further step forward, regimes of truth and the problem of government open up spaces for reflecting on the constitution of subjectivities (see Senellart 2014, in GL), the so-called ethical phase of Foucault’s work. The abandonment of ideology combines here with the issue of subjectivation, which challenges a theory of the ahistorical and monolithic subject and explores the constitution of diverse subjectivities within the subject himself, along with historical and contingent formations.

Therefore our questions are the following: how do discursive formations arise to fabricate the ‘reality’ of leadership? What are the epistemic premises, the regimes of truth that define leadership? Which kind of subjectivation encapsulates head teachers through technologies of governmentality? What freedom can be practiced? There is space for ethical choices? What alternative truths are in play to resist against neo-liberal education policies?

Discourses and contexts of educational leadership

In the last decades the education field has seen a flourishing of approaches and theories on leadership that have increasingly made possible to talk of adjectival leadership, while there has been a shift from administrative to management studies to knowledge about leadership.

In this contribution the analysis of leadership regime of truth is stressed using two dimensions of discursive formations: the scientific paradigms and the enlarged system of leadership knowledge (savoir). The first dimension refers to Seddon’s (1994) distinction between ‘categorical’ and ‘relational’ education contexts. The other discursive dimension refers to the classical tripartition between divergent discourses: welfarism and bureau-professionalism (Clarke and Newman 1997); neo-liberal managerialism (Thrupp and Willmott 2003); and democratic-critical (Grace 1995; 2000).

In this perspective, it is possible to identify three different discourses within which distinctive conceptions of distributed leadership have been developed. The welfarist bureau-professionalism, or welfarism, which emphasizes both the requirements of formal and procedural rationality and the legitimacy and autonomy of professional expertise. The neo-liberal managerialism, which promotes the introduction of efficiency and quasi-marketization for the provision of public services and the management of public administration. The democratic-critical discourse, whose distinctive features are progressively emerging as a reaction to neo-liberal policies.

Following Serpieri (2008) and his further elaboration of the idea of context (Serpieri, Grimaldi and Spanò 2009), we distinguish here between two different types of contexts:

- a) individual-interactive contexts, where the focus is on leadership-style or social interactions among leaders and followers: human actors are at the ground of ontological presumptions;

- b) network-practices contexts, where the subject is decentred in favour of an ontology of praxis and the re-production of practice is understood as a complex process in which human agents, institutions, cultures and material artefacts intertwine and influence each other.

The map presented in Tab. 1 allows us to classify texts and interpreters of leadership through the intersection of discourses and contexts, sort of a guide through the labyrinth of leadership theories and conceptions.

Tab. 1. Discourses and contexts of educational leadership

| Discourse

Context |

Welfarist (Bureaucratic-professional) | Neo-liberal

(Managerialist) |

Democratic

(Critical) |

| Categorical:

individual-interactive |

– Instructional

– Moral |

– Transformational

– System Leadership – Distributed (or to be distributed?) |

– Styles (of micropolitics)

– Micropolitics – Collaborative |

| Network-practices | – Sustainable

– Distributed (in practice)

|

? |

– Feminist

– Greedy leadership work (distributed) – Ecological – Democratic – Configuration – No leadership at all (neo-liberal tiranny) |

Leadership: a neo-liberal ‘dispositif’?

The dispositif bears on the relationship between regimes of truth, technologies of governmentality, and forms of subjectivation and, as for the wonderful metaphorical definition proposed by Deleuze (1999), it cannot be interpreted simply as an heterogeneous assemblage of disparate elements, but it is also traversed by a dynamic field of relations, to allow some approximation of a particular preponderance or balance of forces at a given time creating both subjects and objects.

In a recent work focusing on policy dispositif neo-liberal education policy dispositif in England, Bailey (2013) recalls the scalar dimension of a dispositif that can be located both at the micro and at the macro level. Foucault himself has insisted on the movement between those different levels of analysis, at the moment when his ‘strategic’ conceptualisation of power was prevailing.

In this respect, leadership can be understood as a policy dispositif that produces its effects both at the macro level (from accountability to quasi-market, etc.…), and at the micro levels of organisation and management in every single school. Neo-liberal education has involved a ‘Transnational Leadership Package’, made of theories, paradigms, methodologies and techniques; using a single word: a ‘discourse’ of leadership, that has crossed over borders, contexts of national educational systems, subverting the traditional ‘field of Educational, Leadership, Management and Administration’ (Thomson, Gunter and Blackmore 2013: viii). More specifically, the leadership design (Gronn 2003) of neo-liberal education is instrumental toward aims of entrepreneurship, competition and selection.

In our map, it can be noticed that different conceptions and approaches to leadership representative of a managerialist discourse avoid the serious questioning of educational context and adopt ontologies based on human, especially leadership qualities and interaction with followers.

In this sense, the case of distributed leadership is exemplar if one traces its continuity with transformational leadership that originates from business management during the ‘70s and the ‘80s. At the beginning of the ’90s in fact Leithwood fully develops his concept of transformational leadership, focusing on its fundamental role for improving school contexts through professional expertise and innovation. A ‘transformative’ leader, simply defined, is a person who can guide, motivate and influence others to bring about a fundamental change. This is a conception that still presents a large amount of voluntaristic and heroic individualism, focused on a leader who aims at developing a shared organisational vision. Leithwood, being a ‘smart’ managerialist, recycles this idea in most recent explorations of distributed leadership. As a matter of fact, he tries to pin his label on this innovative approach in his most recent handbook with an introduction entitled ‘New Perspectives on an Old Idea’ (Leithwood et al. 2009). The old idea is nothing more than the process of values sharing already reported in his transformational leadership approach and now readapted to the distributed perspective.

Another effort to reinvigorate distributed leadership has been made by Harris (2008a; 2008b), whereas she has tried to explicitly mark the distance from the excesses of managerialism. This marking implies a contextual and a distributing shift. In fact on the one side Harris tries to re-connect her understanding of distributed leadership to the broader socio-economic and political environments, highlighting their influence on schools’ performances. On the other side, she presents herself as the ‘champion’ of distributed leadership in a managerialist vein. Not by chance Harris, following a functional and pragmatic approach, adapts distributed leadership to education policies actually focused on external accountability, standardisation and schools competition as levers for improvement. Nonetheless, a careful examination of her extended works highlights how those shifts regard the surface’ of her conception of distribution. For the case of the contextual shift, Thrupp and Willmott sarcastically criticize Harris’s effort to re-contextualize distributed leadership arguing how her recent works ‘exhibit the […] tension of promoting the importance of context while presenting a largely decontextualized analysis’ (2003: 102). Intentionally or not, leadership seems to become the end rather than the means, and more specifically a depoliticized and decontextualized end.

In fact Harris’s conception of distributed leadership actually differs ontologically and epistemologically from Spillane’s one because this author could be seen as an interpreter of the welfarist discourse with a deeper and thick interest about educational contexts. Distributed leadership is conceived in terms of practice (Spillane, 2006), that is as interactive processes among human actors and non-human actors as routines, artefacts and so on, that mediate interactions themselves (Gronn, 2000). On the contrary, Harris relates distributed leadership to interactions between leaders and followers where the latters become holders of ‘bits’ of leadership, on the basis of a desirable explicit organisational design provided by the leader herself, that focuses and stresses the positional aspects of social structure, roles and procedures. Thus, distributed leadership continues to be conceptualized within a functionalist frame as a response to the organisational school leaders’ needs.

It seems clear how this knowledge is connected to practices of head teacher’s selection, training, evaluation and promotion that explicitly recall knowledge(s) that subjectivate leaders as school managers, whose organisation and objectives are flattened on the model of educational enterprise. To discuss about this leadership dispositif that subjectivates the head teachers enabling them to redesign the educational context, both external and within the school, and where what strategically count are personal ‘super’ qualities, sort of a clever puppet master of distributed leadership, Niesche (2011: 18) observes:

The dominant paradigms of leadership through heroic performances, leader designer frameworks and best-practice models that are so pervasive have little or no rigorous theoretical underpinnings, and as such the feasibility of these ‘more traditional’ approaches in terms of providing a means for critical self-reflection needs to be seriously questioned.

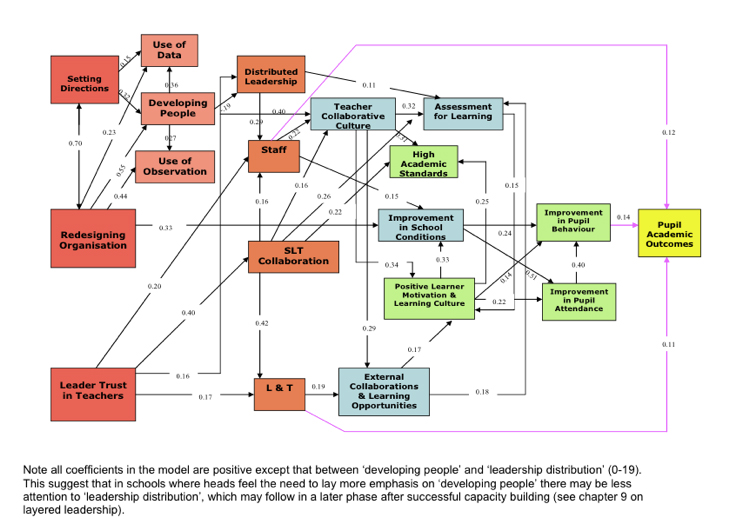

Fig. 1 Heads Perceptions of Leadership Practices and Change in Pupil Outcomes over Three Years (source Day et al., 2009)

Leadership deconstruction

Leadership as policy dispositif, of which transformational and distributed are probably the most relevant ones, produces a regime of truth and technologies of governmentality to put in practice a neo-liberal education model pursuing educational goals congruent with those of competitiveness, selection, performativity and so on. In such a way it subjectivates head teachers, teachers, students and families as entrepreneurs of themselves.

Nevertheless, studies that are inspired by a democratic-critical discourse show a much more complex and articulated knowledge of educational ‘reality’, where the work distribution, or division of labour between professionals causes a ‘greedy’ work for educational leaders and their staff (Gronn, 2003; Thomson, 2009).

Critical knowledge(s) about leadership countervail neo-liberal knowledges on the one side, adopting more sophisticated conceptions focused on a democratic idea of leadership significantly ‘engaged’ in a structural and cultural educational context, as for the case of Woods’ democratic leadership (2005) inspired by Archer’s morphogenesis. On the other side, critical contributions conceive of the leadership dispositif just as one of the tyrannies (along with accountability, performativity, and so on) of neo-liberal education, as witnessed by the absence of the leadership theme in the ‘critical’ Handbook of Sociology of Education (Apple, Ball, Gandin, 2010).

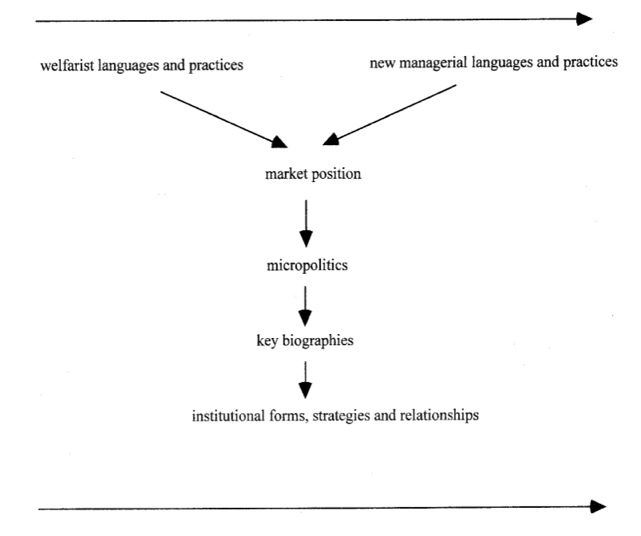

This is the case of Ball and his colleagues, who more recently have developed an interpretation of leadership as imbricated into discursive formations and educational contexts, that Gunter has signalled as an original way of ‘not researching leadership’ (2013). Thus, in researches conducted on the shifting from welfarist to neo-liberal discourse (Gewirtz and Ball 2000), the head teacher is conceived as discursive catalyst in school contexts (Fig 2). Such understanding of school leadership refers to sophisticated and thick descriptions of head teachers’ and teacher’s biographies, seen as a key interpretative dimension useful to understand the shift of the welfarist discourse toward the neo-liberal ones.

Fig. 2 Discursive Shift (Source Gewirtz and Ball 2000)

Such ‘key biographies’ do not play any causal role, as for the neo-liberal leadership dispositif, meanwhile are rather intended to show how school contexts change through complex, non-linear and contingent processes. A genealogical interpretation of problematisations is put into play: and biographies show how some processes of re-subjectivation are not ideological, but catalyse, code and recode and enact diverse educational truths.

A precious contribution in this direction comes from recent researches on policy-enactments in schools (Ball et al. 2012), where it is important to: ‘taking context seriously’, together with ‘policy artefacts’, ‘discourses, representations and translations’.

Thus, policy enactment involves creative processes of interpretation and recontextualisation – that is, the translation of texts into action and the abstractions of policy ideas into contextualised practices – and this process involves ‘interpretations of interpretations’ (…), although the degree of play or freedom for ‘interpretation’ varies from policy to policy in relation to the apparatuses of power within which they are set and within the constraints and possibilities of context. Policies are not simply ideational or ideological, they are also very material (Ball et al 2012: 3).

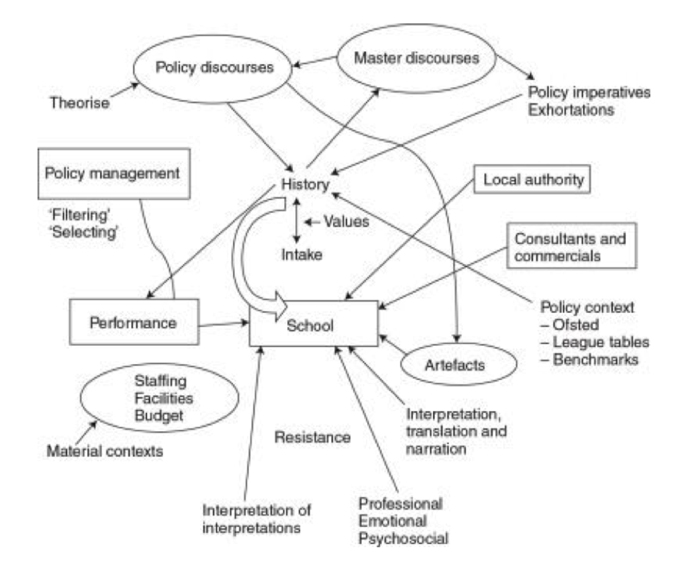

These researchers, inspired by practice epistemology and ontology (where processes and non human actors do matter) and democratic and critic discursive formation, do not leave space for leadership as dispositif in a neoliberal way. They show how some roles are enacted by educational professionals, such as ‘narrators’, ‘entrepreneurs’, ‘transactors’, ‘translators’, and so on, but there are no any leaders (49). In other words, they propose a ‘leadership configuration’ (Gronn 2010), that is a plurality of roles or, even better, a ‘contextual configuration’, historically situated, and ‘mobile’, open to ethical freedom and creativity (Revel 2015) in a foucauldian way. Moreover, the authors construct a map of such a school configuration where, paradoxically, both leader and leadership disappear (Fig. 3).

[W]e offer a visual account of our thinking about policy enactment… The school represents our starting point; it is central but not necessarily in the centre, its history and intake (and connected values) are central too but also fragile. In the diagram, the school looks embattled – all those arrows bearing down on it – but those are also its components, such as the material context of staffing, facilities and budgets and the diverse discourses and policies that constitute the school. Performance looms large – although the size of the boxes carries no particular meaning – and its specific construction is shaped by the institutional ‘management’ of policy. History, intake and values mediate policy, policy contexts and discourses, as they find expression in the school. There is a lot of human action in this diagram: policy interpretation and translation (as well as interpretations of interpretations); professional and emotional dimensions; and the filtering and doing of policy work. There is also resistance, and we left this aspect deliberately unconnected, as its expression in murmuring and discontents […] are to some extent free-floating, rather than systematic. Neither the model, nor the account of the model we are giving here is comprehensive or finished. […] A model that is in flux like this and that can develop into its own dynamic is exactly what we had in mind (Ball et al. 2012: 143)

Such a configuration, which could be labelled ‘without leadership’ (Serpieri, 2008), opens up interesting scenarios that allow us to explore the ‘potentials’ (Gronn, 2009) of a ‘democratic leadership’ (Woods, 2005), in order to deconstruct the neo-liberal dispositif of leadership. This perspective drives us to reflect on the way in which head teachers can carry on their discourse about leadership: critical, resistant, and bearer of truths that are different from the neo-liberal discourse; but also to explore the ethical spaces of freedom (Laidlaw, 2014), that let head teachers to enact a parrhesiastic life (Ball, 2015; Ball and Olmedo 2013). However, foucauldian lesson reminds us that an escape from dispositif and regimes of truth is never fulfilled and that we will always been subjectivated through diverse technologies of governmentality: according to our ethical choice of practicing a ‘courage of truth’ (CT), to think other ‘possibilities’ (Ball 2013) for exploring more democratic leadership configurations outside of neo-liberal policy dispositif. This is a lesson that goes beyond ideological petitions and presumptions.

Fig. 3 Thinking about Policy Enactment (source Ball et al. 2012)

References Althusser, L. (1971) [1970] ‘Ideology and Ideological Apparatuses’, in Althusser, L. Lenin and Philosophy, London: New Left Books. Ball, S.J. (2013) Foucault, Power, and Education, New York & London: Routledge. BBP (2008) The Birth of Biopolitics: lectures at the Collège de France, 1978-1979, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Buci-Glucksman, C. (1975) Gramsci et l’Etat, Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard. Deleuze, G. (1999) Foucault. London: Continuum. Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and punish, London: Penguin. GL (2014) On the Government of the Living: lectures at the Collège de France, 1979-1980, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Gronn, P. (2009) ‘Ibryd Leadership’, in Leithwood K., Mascall B., Strass T. (eds.) Distributed Leadership According to the Evidence, New York: Routledge. Harcourt, B.E. (2015) ‘Course Context’, in Foucault, PS. Olssen, M. (1999) Michel Foucault: materialism and education, Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers. PS (2015) The Punitive Society: lectures at the Collège de France, 1972-1973, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. Revel, J. (2015) Foucault avec Merleau-Ponty. Ontologie politique, présentisme et histoire, Paris: Vrin. Senellart, M. (2014) ‘Cours Context’ in Foucault, GL. Serpieri, R. (2016) Discourses and contexts of leadership, in Samier, E. (ed) Ideology of Educational Administration and Leadership, New York & London: Routledge. STP (2007) Security, Territory, Population: lectures at the Collège de France, 1977-1978, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. TP [1977] (1980) ‘Truth and power’, in Gordon, C., (ed) Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writins 1972-77, Brighton: Harvester Press.